Germ Theory

The germ theory is a fundamental tenet of medicine that states that microorganisms, which are too small to be seen without the aid of a microscope, can invade the body and cause certain diseases.

Until the acceptance of the germ theory, many people believed that disease was punishment for a person's evil behavior. When entire populations fell ill, the disease was often blamed on swamp vapors or foul odors from sewage. Even many educated individuals, such as the prominent seventeenth century English physician William Harvey, believed that epidemics were caused by miasmas, poisonous vapors created by planetary movements affecting the Earth, or by disturbances within the Earth itself.

The development of the germ theory was made possible by the certain laboratory tools and techniques that permitted the study of bacteria during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

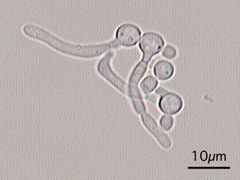

The invention of primitive microscopes by the English scientist Robert Hooke and the Dutch merchant and amateur scientist Anton van Leeuwenhoek in the seventeenth century, gave scientists the means to observe microorganisms. During this period a debate raged among biologists regarding the concept of spontaneous generation.

Until the second part of the nineteenth century, many educated people believed that some lower life forms could arise spontaneously from nonliving matter, for example, flies from manure and maggots from decaying corpses. In 1668, however, the Italian physician Francisco Redi demonstrated that decaying meat in a container covered with a fine net did not produce maggots. Redi asserted this was proof that merely keeping egg-laying flies from the meat by covering it with a net while permitting the passage of air into the containers was enough to prevent the appearance of maggots. However, the belief in spontaneous generation remained widespread even in the scientific community.

In the 1700s, more evidence that microorganisms can cause certain diseases was passed over by physicians, who did not make the connection between vaccination and microorganisms. During the early part of the eighteenth century, Lady Montague, wife of the British ambassador to that country, noticed that the women of Constantinople routinely practiced a form of smallpox prevention that included "treating" healthy people with pus from individuals suffering from smallpox. Lady Montague noticed that the Turkish women removed pus from the lesions of smallpox victims and inserted a tiny bit of it into the veins of recipients.

While the practice generally caused a mild form of the illness, many of these same people remained healthy while others succumbed to smallpox epidemics. The reasons for the success of this preventive treatment, called variolation, were not understood at the time, and depended on the coincidental use of a less virulent smallpox virus and the fact that the virus was introduced through the skin, rather than through its usually route of entry—the respiratory tract.

Lady Montague introduced the practice of variolation to England, where physician Edward Jenner later modified and improved the technique of variolation. Jenner noticed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox on their hands from touching the lesions on the udders of cows with the disease rarely got smallpox. He showed that inoculating people with cowpox can prevent smallpox. The success of this technique, which demonstrated that the identical substance need not be used to stimulate the body's protective mechanisms, still did not convince many educated people of the existence of disease-causing microorganisms.

Thus, the debate continued well into the 1800s. In 1848, Ignaz P. Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician working in German hospitals, discovered that a sometimes fatal infection commonly found in maternity hospitals in Europe could be prevented by simple hygiene. Semmelweis demonstrated that medical students doing autopsies on the bodies of women who died from puerperal fever often spread that disease to maternity patients they subsequently examined. He ordered these students to wash their hands in chlorinated lime water before examining pregnant women. Although the rate of puerperal fever in his hospital plummeted dramatically, many other physicians continued to criticize this practice as being useless.

In 1854, modern epidemiology was born when the English physician John Snow determined that the source of cholera epidemic in London was the contaminated water of the Broad Street pump. After he ordered the pump closed, the epidemic ebbed. Nevertheless, many physicians refused to believe that invisible organisms could spread disease.

The argument took an important turn in 1857, however, when the French chemist Louis Pasteur discovered "diseases" of wine and beer. French brewers asked Pasteur to determine why wine and beer sometimes spoiled. Pasteur showed that, while yeasts produce alcohol from the sugar in the brew, bacteria can change the alcohol to vinegar. His suggestion that brewers heat their product enough to kill bacteria but not yeast, was a boon to the brewing industry—a process called pasteurization. In addition, the connection Pasteur made between food spoilage and microorganisms was a key step in demonstrating the link between microorganisms and disease. Indeed, Pasteur observed that, "There are similarities between the diseases of animals or man and the diseases of beer and wine." The notion of spontaneous generation received another blow in 1858, when the German scientist Rudolf Virchow introduced the concept of biogenesis. This concept holds that living cells can arise only from preexisting living cells. This was followed in 1861 by Pasteur's demonstration that microorganisms present in the air can contaminate solutions that seemed sterile. For example, boiled nutrient media left uncovered will become contaminated with microorganisms, thus disproving the notion that air itself can create microbes.

In his classic experiments, Pasteur first filled short-necked flasks with beef broth and boiled them. He left some opened to the air to cool and sealed others. The sealed flasks remained free of microorganisms, while the open flasks were contaminated within a few days. Pasteur next placed broth in flasks that had open-ended, long necks. After bending the necks of the flasks into S-shaped curves that bent downward, then swept sharply upward, he boiled the contents. Even months after cooling, the uncapped flasks remained uncontaminated. Pasteur explained that the S-shaped curve allowed air to pass into the flask; however, the curved neck trapped airborne microorganisms before they could contaminate the broth.

Pasteur's work followed earlier demonstrations by both himself and Agostino Bassi, an amateur microscopist, that silkworm diseases can be caused by microorganisms. While these observations in the 1830s linked the activity of microorganisms to disease, it was not until 1876 the German physician Robert Koch proved that bacteria can cause diseases. Koch showed that the bacterium Bacillus anthracis was the cause of anthrax in cattle and sheep, and he discovered the organism that causes tuberculosis.

Koch's systematic methodology in proving the cause of anthrax was generalized into a specific set of guidelines for determining the cause of infectious diseases, now known as Koch's postulates. Thus, the following steps are generally used to obtain proof that a particular organism causes a particular disease:

- The organism must be present in every case of the disease.

- The organism must be isolated from a host with the corresponding disease and grown in pure culture.

- Samples of the organism removed from the pure culture must cause the corresponding disease when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible laboratory animal.

- The organism must be isolated from the inoculated animal and identified as being identical to the original organisms isolated from the initial, diseased host.

By showing how specific organisms can be identified as the cause of specific diseases, Koch helped to destroy the notion of spontaneous generation, and laid the foundation for modern medical microbiology.

Koch's postulates introduced what has been called the "Golden Era" of medical bacteriology. Between 1879 and 1889, German microbiologists isolated the organisms that cause cholera, typhoid fever, diphtheria, pneumonia, tetanus, meningitis, gonorrhea, as well the staphylococcus and streptococcus organisms.

Even as Koch's work was influencing the development of the germ theory, the influence of the English physician Joseph Lister was being felt in operating rooms. Building on the work of both Semmelweis and Pasteur, Lister began soaking surgical dressings in carbolic acid (phenol) to prevent postoperative infection. Other surgeons adopted this practice, which was one of the earliest attempts to control infectious microorganisms.

Thus, following the invention of microscopes, early scientists struggled to show that microbes can cause disease in humans, and that public health measures, such as closing down sources of contamination and giving healthy people vaccines, can prevent the spread of disease. This led to reduction of disease transmission in hospitals and the community, and the development of techniques to identify the organisms that for many years were considered to exist only in the imaginations of those researchers and physicians struggling to establish the germ theory.

See also Vaccine.

Marc Kusinitz

Additional topics

Science EncyclopediaScience & Philosophy: Gastrula to Glow discharge